Hype:

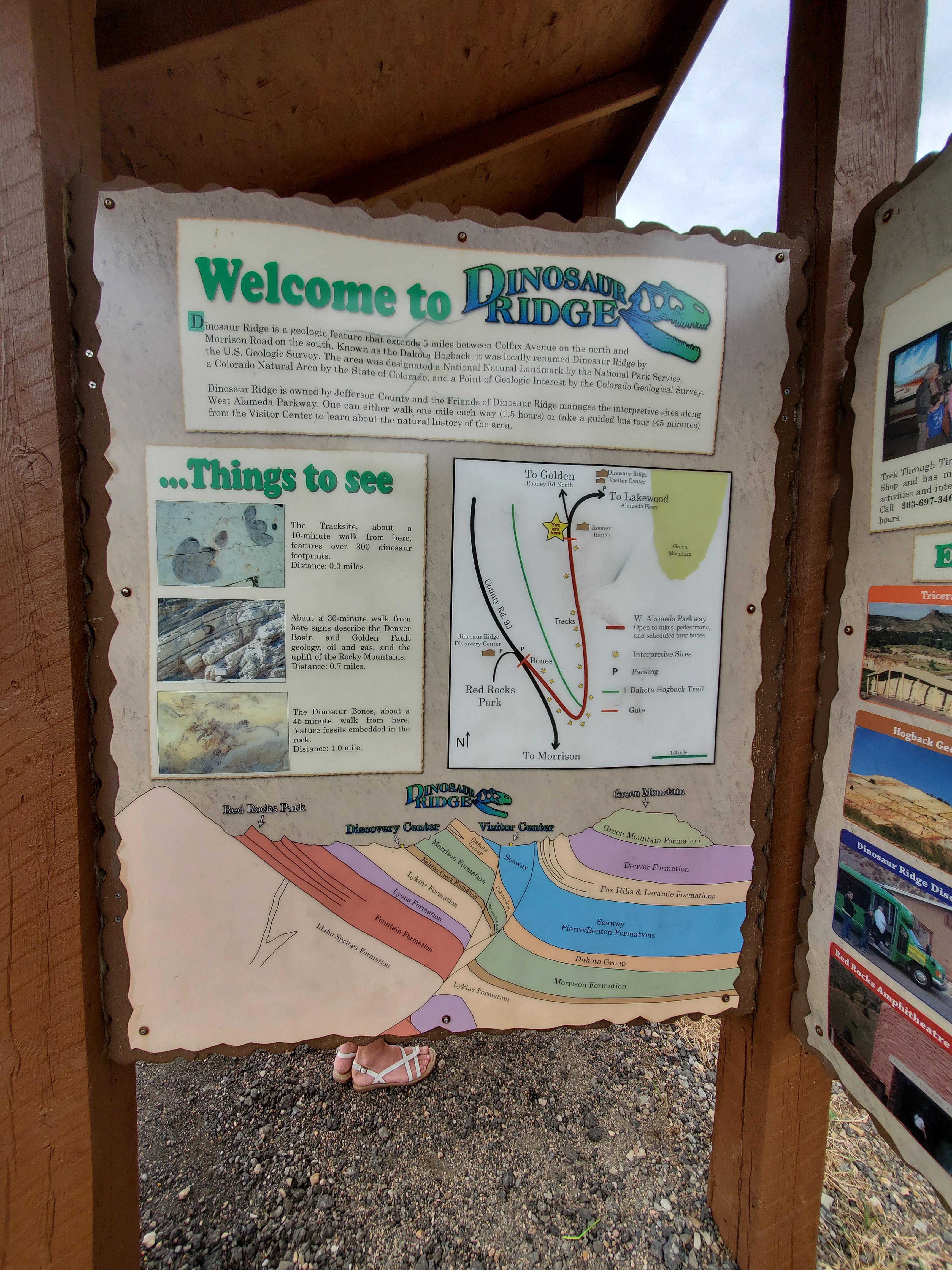

The Dinosaur Ridge walking tour is located along a stretch of road that is now closed. Only buses from one of the guide companies are allowed to drive on the road because before the road was closed, the high traffic combined with heavy pedestrian use was too dangerous. Now, visitors can walk the 1.1-mile route, stopping at more than a dozen interpretive stops along the way. Dinosaur ridge features hundreds of dinosaur tracks and a few fossilized dinosaur bones as well as geological and other information. Some of the best-known dinosaurs were found here, including Stegosaurus, Apatosaurus, Diplodocus, and Allosaurus. In 1973, the area was recognized for its uniqueness as well as its historical and scientific significance when it was designated the Morrison Fossil Area National Natural Landmark by the National Park Service.

Trail Condition: Class 1 (Trail is either paved or gravel. Navigation skills are not needed because there is only one trail or because there are signs. Elevation gains are gradual or there are stairs.)

Time: 1.5-2 hours

Length: 2.2 miles round trip

Elevation Gain: 400 ft

Fees: An audio tour is available for purchase at the Dinosaur Ridge visitor center

Recommended Ages:

| 0-3 |

| 4-11 |

| 12-19 |

| 20-49 |

| 50-69 |

| 70+ |

Recommended Months to Visit:

| Jan |

| Feb |

| Mar |

| Apr |

| May |

| Jun |

| Jul |

| Aug |

| Sep |

| Oct |

| Nov |

| Dec |

Navigate to 39.686240, -105.193094.

Welcome to Dinosaur Ridge!

This is the East Gate Kiosk starting point located near the Dinosaur Ridge Main Visitor Center.

On your journey today you will learn about the lives and deaths of our backyard dinosaurs and the different environments they roamed. This audio tour will describe and interpret 13 stops, indicated by posted signs as you walk along the 1 1/10 mile Dinosaur Ridge paved trail. We recommend that each member in your party download the tour to their own device for a more individual self-paced tour experience.

Please be prepared to walk 2 1/2 miles round-trip with an uphill climb for half of your journey. THERE ARE NO FACILITIES OR WATER ALONG THE TRAIL (with the exception of one port-a-potty near the top of the curve). Be sure to dress for the changing weather and bring sunscreen and water with you.

NOTE: for your safety, pedestrians must walk in the designated lane closest to the mountainside. The outermost lane is used by bicyclists, who often travel at high speeds over Dinosaur Ridge. Please observe all posted signs and beware of rattlesnakes coming out of hibernation. Climbing and collecting are NOT allowed. Dinosaur Ridge fossils are protected by the state of Colorado as Dinosaur Ridge is a National Natural Landmark and a unit of the National Park System.

This audio tour was created by the nonprofit Dinosaur Ridge organization. To learn more about how you can support our efforts in protecting these unique resources, visit our website at www, dot dinoridge, dot org.

You may begin your walk on the inside lane uphill to the next stop, the Western Interior Seaway. As you begin your walk, here is some information:

Dinosaur Ridge is part of the Dakota Hogback, the prominent ridge that parallels the Front Range of Colorado’s mountains. The term “hogback” is used in geology as a hill with a narrow crest and steep slopes on both sides that is capped by harder ragged rock.

Dinosaur Ridge is made of layered sedimentary rocks called sandstone and mudstone. The softer mudstone erodes quicker than the harder sandstone, which you can see when looking to the top of the ridge.

These layers on the east side up to the crest are 100 million years old, the beginning of the Late Cretaceous (the last period of the Age of Dinosaurs). During this period, the Front Range was not mountainous, but a shoreline with sandy beaches and flats where prehistoric critters walked and left behind thousands of traces.

The layers on the West Side are underneath and older than the beach layers, at 150 million years old, and are the last layers of the Jurassic Period (the middle period of the Age of Dinosaurs). The rocks show a semi arid floodplain with seasonal rivers and lakes, and more tracks from dinosaurs and even their bones can be seen.

Welcome to the Western Interior Seaway

Imagine flying across Colorado and below you is a vast inland sea. The evidence is these flaking layers of shale, once thin blankets of soft mud deposited layer by layer at the bottom of this sea. The middle of North America was shaped like a bowl as the Rocky Mountains hadn’t yet uplifted. Between 120 million and 95 million years ago, a vast inland sea spread through this lower area covering the middle of the continent with a saltwater seaway. This was called the Western Interior Cretaceous Seaway.

The Cretaceous was a period of time that stretched 145 million to 65 million years ago. It is the last period of three in the Mesozoic Era, the Age of Dinosaurs.

Sidenote: A formation is a group of layers of a similar age and type.

The gray shale covering this slope is the Benton Formation (better known as the Benton Shale), which was originally layers of mud and organic material that settled in thin layers on the bottom of the Western Interior Seaway. When these layers were deposited around 92 million years ago, the seaway was at maximum extent, covering Colorado entirely. Water on the globe was the highest at this point as no ice caps were located at the poles due to the warm nature of the planet at the time.

The Benton Shale is around 500 feet thick, and the layers are a treasure-trove of fossils! Bones and scales from small fish scatter among shells of palm-sized ammonites, clams, and oysters. Larger carnivores such as swimming reptiles called mosasaurs and plesiosaurs are rare here, but are abundant elsewhere in Colorado. Please do not do any collecting here, our fossils are protected under our National Natural Landmark distinction as part of the National Park Service.

Walk uphill on the inside lane to the next stop at CROCODILE CREEK.

Welcome to Crocodile Creek

The most abundant predator tracks in these 100 million-year-old rock layers were not made by dinosaurs, they were made by crocodiles. Here at the sign, take a look up the slope and see if you can find these distinctive claw marks. On the middle boulder just before you are three, parallel grooves about the size of your hand. These grooves were made by the clawtips of a Colorado croc!

Geologists and paleontologists use rocks as well as fossils of plants and animals to help reconstruct ancient environments and climates that existed in the past. These sedimentary rocks contain plant impressions, tracks of dinosaurs, crocodiles, worms, and shrimp, ripple marks and fossilized mats of algae. Where you’re standing was a tidal channel. Look to the right and left and you can see the sloped edges of the channel dipping toward you.

During high tide, this channel filled with water and brought out filter-feeding critters buried in the sand such as clams. If you move to your left, uphill from the Crocodile Creek Sign, the pits and small circular dents in that top layer were made by burrowing shelled crustaceans and worms. Lingering on the sides of the channel and on bars of sand in the middle were 6-10 foot long crocodiles. Dozens of crocodile swim and walking traces have been found in the Dinosaur Ridge area, and it seems that these predators were quite abundant in Colorado 100 million years ago.

As you walk uphill a little, you’ll see a rusty brown surface with criss-cross, and zig-zagging grooves, and to the left of this surface near a small tree is another interpretive sign. These lines are tree-branch and root impressions that may have washed in during a stormy afternoon. In the middle of this section are two dug-in areas side by side. They are scratch marks made by a meat-eating dinosaur.

Though this is only such scratch impression of it’s kind found at Dinosaur Ridge (so far), around thirty were uncovered in western Colorado in rocks of the same age. Those impressions are evidence of a group nest-building behavior that is seen in some ground-nesting birds today. This behavior is called lekking. This new 2016 discovery seems to indicate that modern birds may have inherited this behavior from their dinosaur ancestors.

To see more evidence of this prehistoric beach environment continue walking uphill to the RIPPLE MARKS stop.

Welcome to the Slimy Beach & Ripple Marks!

Ancient beaches covered with wave-rippled sand form the first rocky layers of these foothills.

Moving water left behind ripples in the sand of a flat beach nearly 100 million years ago. These sedimentary structures are not fossils but serve as a remnant of waves washing along this ancient shoreline.

Some sections of the beach, like this spot, were blanketed by washed-up mats of once-floating algae. Waves ripped at the sun-dried algae exposing the sand below. Further wave action shaped the sand to create this patchwork of ripple marks. Similar algal mats and rippled beaches can be found in modern shallow coastal areas of Florida and California.

To see more evidence of the dinosaurs and other creatures that called Colorado home, continue walking on the inside lane uphill to the large blue structure and fenced-in area, the DINOSAUR TRACK SITE Stop.

Welcome to the Dinosaur Ridge Track Site! #1

This track site is rated #1 in the nation by paleontologists and is visited annually by over 245,000 visitors! Take a moment to observe the tracks, the shapes and sizes, the direction of travel, as well as the number of tracks found on this hillside. It’s an amazing place!

The layers and tracks were exposed by road construction in the late 1930s, and unfortunately the track discoveries that put the Dakota Hogback in the limelight are now gone, either eroded or vandalized. These tracks were revealed in the 1950s or 60s as softer mudstone weathered away.

What was this spot like 100 million years ago? Tidal waves or large coastal storms deposited alternating layers of sand and mud overtop these once flat beaches, and the ancient mud from this smelly marsh squished between the toes of our track makers. Unlike the ripple-covered surface downhill, this spot was farther from the waves as indicated by lack of ripple marks and the fact that the tracks weren’t washed away.

How were these tracks made? It’s not as easy as “dinosaurs walked by”. The layers of sand you’re looking at were actually covered by a layer of mud - and that’s where the dinosaurs were stepping.

Tromping through this muddy marsh were dozens of dinosaurs of different sizes, their weight squishing deep into the buried, mud-covered sand. This left behind an underprint - a secondary track made in the sand underneath the natural track layer in the mud.

Uplift, erosion, and man-made construction exposed the sand layer covered in underprints for the world to see 1936. This was the first exposure of our world-famous tracks! So what makes us #1? One of those reasons is that we have four different track makers, three dinosaurs and one crocodile, and over 300 tracks made by 37 individual animals!

Dinosaur Track Site Part 2: Our Track Makers

We encourage you to examine the tracks up close and wonder what life might have been like for the creatures that lived along this ancient beach. However, for your safety with respect to the COVID-19 virus, we are asking visitors to NOT TOUCH THE TRACKS OR ROCKS.

Head into the gated area to get a closer look at our tracks! Please only allow one group at a time inside the gated area, and maintain a distance of six feet from non-related parties.

The common track-maker here was a type of hadrosaur, or duck-billed dinosaur. These elephant-sized animals weighed around three tons and were between 20 and 25 feet long. Their tracks are identified by three rounded toes with feet as wide as they are long. At the far end of this viewing space you can see large and small tracks side by side.

Several trackways of ostrich-sized carnivorous dinosaurs are scattered across the Track Site. We call them ornithomimids, meaning bird-mimic. These smaller tracks are identified by three, pointed and narrow toes. You can see one of these trackways just below the hadrosaur tracks near the sidewalk.

Two or three tracks of a large carnivorous dinosaur have been identified, but are not viewable from this spot. There’s not much evidence locally of large predatory dinosaurs 100 million years ago, so it’s tough to say which could have made these tracks. The closest fossils that could fit our track maker come from Oklahoma and Texas of a dinosaur called Acrocanthosaurus - the high-spined lizard. Imagine a slightly bigger Allosaurus, as the two dinosaurs were related though separated by nearly 50 million years.

Swim tracks from a single crocodile around six feet long are in a slightly lower layer near the gate entrance to this area. Metal banding is a preservation technique, and can be seen around the edge of the crocodile track layer. In the center is a big hole that was made by dynamite from road construction!

This and many other sites around the world give us a glimpse into a “day in the life” of a dinosaur. To ichnologists, scientists who study trace fossils, track sites like this one offer a chance to study more than just the number of toes and foot-shapes of these ancient animals.

The skinny-toed carnivores have a greater distance between the tracks for their size suggesting that they moved at a faster clip than the larger, slower herbivores.

The herbivore tracks are mixed large and small in size and hint at parenting behavior - adults walking with the young. Traveling in small herds likely helped them to keep an eye on their young and protect them from the two predatory dinosaur species as well as those snapping crocodiles.

Dinosaur Ridge and its fossils are protected as a National Natural Landmark. Our experts are working to preserve our one-of-a-kind paleontological and geological resources against the effects of erosion, weathering, and vandalism, and we hope that you will support us in this effort. Visit our website to learn how you can become a supporter or volunteer. A metal donation box is located at the entrance to this site if you would like to make a donation!

To see more fossils and clues, continue uphill for approximately 1/2 mile. There are two sites to see along the way marked by interpretive signs. At the first crosswalk uphill near the wooden entrance to the Dakota Ridge Hiking Trail, please carefully cross the road using the crosswalk while yielding to cyclists. Here you will find the DENVER BASIN OVERLOOK Stop at the blue shade structure.

Welcome to the Denver Basin Overlook

As you face toward the city and away from the mountains, the Denver Basin extends east and north of Dinosaur Ridge. This is called a basin due to the sunken bowl shape of the entire Denver Area. The rock layers of Dinosaur Ridge are still out in front of you, but due to faulting and uplift, shifting and sinking, they are nearly two miles underneath Denver as you look east! Check out the map on the interpretive sign to see a cross-section of the Front Range and out to Denver, and follow the layers of Dinosaur Ridge with your finger to see where they end up.

The hill on the other side of the highway blocking our view of Downtown Denver is Green Mountain. Those layers were deposited after Dinosaur Ridges. The oldest layers are closest to the highway (white or tan outcrops near the base of Green Mountain) and are aged around 75 million years. The layers near the top are aged to 50 million years and are made up of pebbles from the newly formed Rocky Mountains! Hayden/Green Mountain Park is a great place for hiking with a lot of trails. There are beautiful sights and even fossilized tree stumps from right after the age of dinosaurs!

One important thing to know about the geology here is that these layers were tilted during mountain uplift. This uplift started around 70 million years ago and ended around 50 million years ago - so for 20 million years, Colorado was split, faulted, shaken, and cracked as the mountains rose from deep underground. This caused the uplift and tilting of over 300 million years of layers on both sides of the range!

Between Dinosaur Ridge and Green Mountain, nearly following the highway C-470, is the Golden Fault. A fault is a crack in the Earth’s crust where movement occurs, and the crack here shifted and plunged the layers of Dinosaur Ridge downward and underneath younger layers out to the east. This fault is one piece of evidence of the powerful uplift of the Rockies.

To learn more about the rock layers and what they tell us about past environments, please continue along the outside of the curve to the CONCRETION and ASH BED stops.

Welcome to the Concretion!

Take a look above you to the left of the interpretive sign. What interesting feature can you observe? Is that an eyeball up there? Maybe an egg? This is actually a geological feature called a concretion. Concretions form when minerals in groundwater deposit around a pebble or a piece of organic material such as a branch or bone.

The sandstone in the concretion contains more iron than the surrounding layers, and that makes it harder and more resistant to erosion. This is why it stands out like some sort of strange giant marble - though it’s just another sedimentary structure and not a fossil, much like the ripple marks.

Take a moment to look down at the layers near where the road meets the Ridge, and you’ll see a round hole. That’s the spot where another huge concretion weathered out from the surrounding rock. Lucky for us, it broke after the short tumble and we were able to see that a piece of wood was the catalyst. What do you think is in the center of the big one above?

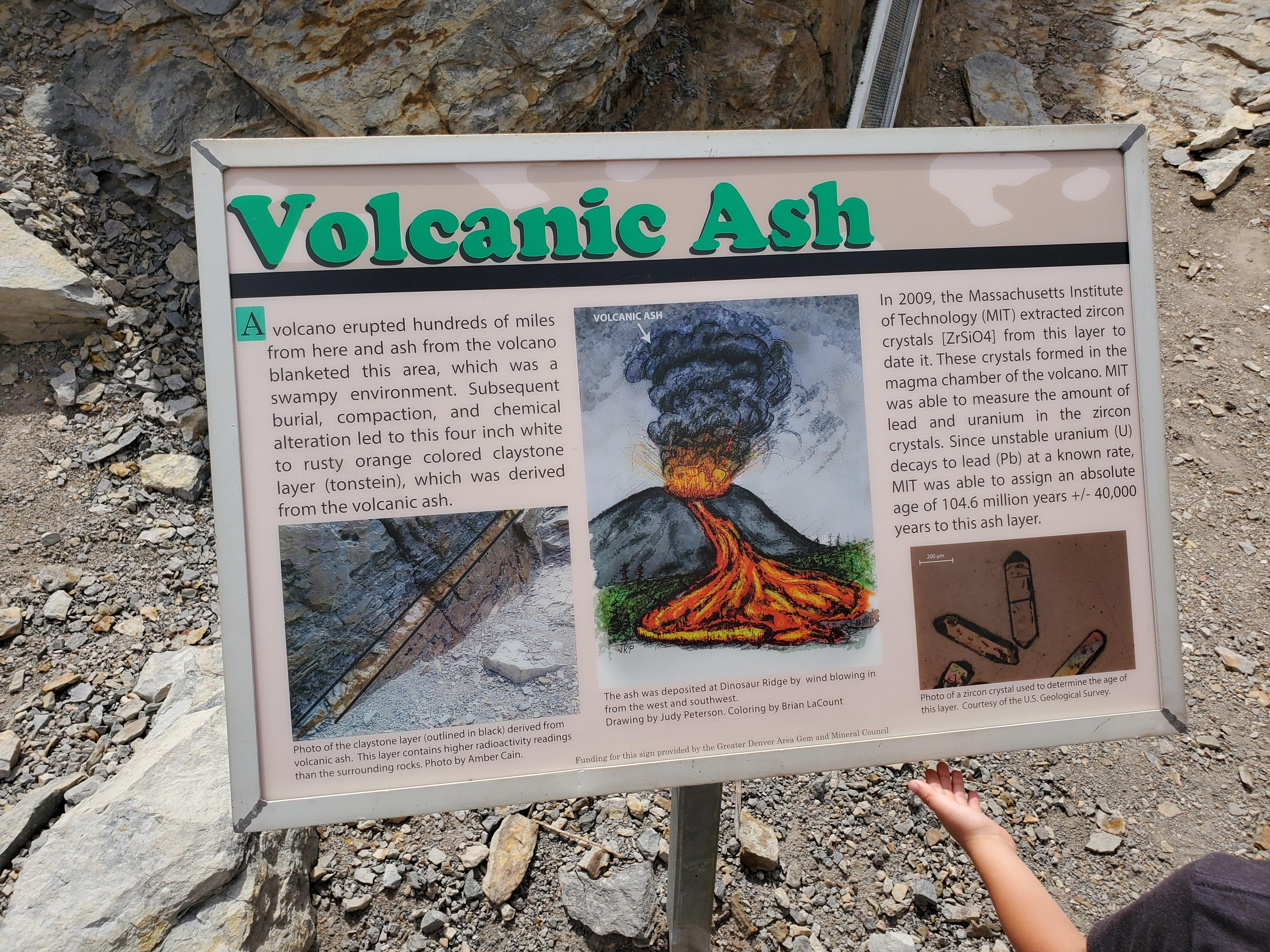

Welcome to the Ash Bed!

As you walk around the curve, take a look at the many layers exposed in these rocks. One that is especially interesting to geologists was identified as a layer of ash deposited by volcanoes that were thought to be in the Sierra Nevadas 100 million years ago. This layer is easy to spot as it is lighter in color and tinged a bit rusty. We have installed a protective barrier along the exposure of the layer as it was unfortunately being picked apart by visitors. This layer of ash is thought to have once been several feet thick, but the sand and mud that piled up squished it down over time to a mere couple of inches!

Why is a layer of ash important? These ash layers are time indicators. The ash contains tiny zircon crystals and inside those tiny crystals are elements of uranium. Uranium can be dated quite accurately in a geochemical laboratory. This process is how we try to get an absolute date for a layer or a fossil, which is hard to do. Mostly in the dating of sedimentary rocks, it’s all relative. The layers above would be considered younger and the layers below would be considered older, and since certain fossils are only found at certain times, we can relatively date the layers around those fossils (or vice versa).

Relative dating does not give an exact age to any of the layers. A good example of this is our Colorado State Fossil, Stegosaurus. In Wyoming, we find this plate-backed dinosaur in rocks with several absolute dates of 148 to 150 million years old. So we can estimate that the Stegosaurus bones found here at Dinosaur Ridge are also around 150 million years old.

The decay of those radioactive uranium elements in the zircon crystals of the ash bed is used to give an absolute age date of 104.6 million years old, (give or take 37,000 years). Considering the vast expanse of geologic time, these absolute dating methods are extremely accurate!

For the next interpretive stop as you move to the west side of the Ridge, please continue walking on the outside of the curve to the other blue shade structure, the RED ROCKS OVERLOOK stop.

Welcome to the Red Rocks Overlook!

Look toward the mountains and notice the beautiful and iconic Red Rocks Park! Between those two jutting formations are the seats of the famous outdoor amphitheater. All of these layers, Dinosaur Ridge included, were here before our mountains broke the surface 75 million years ago, and some of the oldest rocks in Colorado can be found just across this valley.

Sidenote: A formation is a group of layers of a similar age and type.

The granite of Mount Morrison (named for the town just two miles south) sits underneath Red Rocks Park. This is the Idaho Springs Formation, and is igneous rock made mostly of the minerals quartz, mica, and feldspar. At 1 point 7 billion years old, this mountain range spent most of its life deep underground. Around 75 million years ago, the ancient layers rose and cooled causing crystals to form. Breaking the surface at the end of the Cretaceous was our Rocky Mountains.

On top of the granite mountain sits the Fountain Formation. That’s the rocks that make up Red Rocks Park, Red Rock Canyon at Garden of the Gods, the Flat Irons in Boulder, and more along the Front Range. At around 300 million years old, these are thick layers of sandstone deposited during the erosion and breakdown of the Ancestral Rocky Mountains - the range in Colorado that existed and disappeared before dinosaurs walked the Earth.

There are two major formations of rock between Red Rocks and Dinosaur Ridge. The farthest can be seen jutting up as a white or light tan rock surface behind the houses downhill from the red layers. This is the Lyons Formation and is around 280 million years old. Elsewhere we find giant salamanders, sharks, and Dimetrodon, a reptile-like mammal ancestor.

The second, closer formation is a little orange-colored ridge below those houses deeper into the valley. The sides are a rusty orange while the top is a crumbling white. This is the Lykins Formation and is dated to 250 million years. This is the Triassic Period, the first period of the Mesozoic Eria - aka the Age of Dinosaurs! At this time, Colorado was a shallow marine environment. The white crusty rock at the top of that ridge is called stromatolitic limestone, and is composed of fossilized blue-green algae layers.

Welcome to The Bulges!

As you enter the cement ramp area, note the blue poles in an effort to halt erosion. These are the first layers of Dinosaur Ridge’s Jurassic Park! This is the Morrison Formation and was named after the town of Morrison just two miles south. These are some of the last layers of the Jurassic Period laid down around 150 million years ago.

This is a great spot to study the lives of dinosaurs. We encourage you to take a moment to examine these sandstone layers up close, but please do not touch. What do you notice or observe? Can you see the weird lumps sticking down from the sandstone ledge?

At the end of the Jurassic, Colorado was a flat, vast floodplain spiderwebbed with rivers and dotted with ponds. There was no ocean in sight, and it would be nearly 50 million years before this area became beach-front property. When those rivers flooded during the rainy season, similar to today’s monsoonal rains, they would overflow into adjacent ponds where dinosaurs of all shapes and sizes trampled the edges for a drink.

Follow the lines of the rock layers with your eyes. Do you see the downward impressions or bulges? These were made on flat ground by animals sinking and squishing through the wet mud and sand. We see them now from the bottom and side because of uplift and erosion. The evidence in the rock layers here suggest that dinosaurs of different sizes and species were together, perhaps the smaller utilizing the larger for protection, indicating symbiotic relationships.

The largest of these tracks were made by sauropods, otherwise known as long-necked dinosaurs, like Apatosaurus. The Morrison Natural History Museum took measurements of the smaller bulges, seen to the right of the sign. Their paleontologists determined that they were likely made by a different type of dinosaur, a bipedal ornithopod. This was an early ancestor to better-known hadrosaurs, and the best Colorado native to fit these tracks was called Camptosaurus.

To learn more about the lives and deaths of the dinosaurs that once lived in this area, walk on the path downhill to the stop, the MORRISON FORMATION BONE BED Part 1 and 2.

Welcome to the Morrison Formation Bone Bed Part 1

We encourage you to examine the fossil bones up close, but for the protection of you and others, PLEASE DO NOT TOUCH THE BONES OR ROCKS at this time.

There are two easy ways to spot our dinosaur bones. First, do you see the darker colored shapes in the sandstone? The bones absorbed a lot of iron and other minerals during the fossilization process, and are therefore a rusty brown in color. This makes them stand out against the lighter tan of the sandstone. Second, you’ll notice a shape and an edge to the bone. Also found in these sandstone layers are concentrations of iron, otherwise known as iron spots. These will superficially look like body fossils, but do not have the edged shape you should see with a bone.

The Morrison Formation, this section of similarly aged rock, is one of the most prolific dinosaur fossil formations in the world. The end of the Jurassic Period, (148-155 million years ago), was the peak for many different groups of dinosaurs. Jam-packed bone beds are found across the western US in layers of this far-reaching formation. These layers are found in nearly a dozen states and into the southern parts of central and western Canada.

Some of these famous quarries are Dinosaur National Monument in Utah and Thermopolis and Como Bluff sites in Wyoming. Here in Colorado, Dinosaur Ridge shares notoriety with the Garden Park Fossil Areas in Canon City, and the Fruita Paleontological Area just outside of Grand Junction. All of these sites are famous for being graveyards of giants as the Late Jurassic was a time when the largest land animals to exist roamed Colorado. Some species grew to over 100 feet long and weighed in excess of 50 tons!

Welcome to the Morrison Formation Bone Bed Part 2: Bone Discoveries!

Some of the most iconic dinosaurs like Brontosaurus and Diplodocus came from this formation. Dinosaur Ridge is home to the world’s very first Stegosaurus and Apatosaurus specimens, and you can see their bones scattered here in these sandy layers. Other remains include Allosaurus and Camarasaurus, two dinosaur species, and newer discoveries have revealed lungfish, pterodactyl, and turtle fossils. These new discoveries were made by our sister Museum, the Morrison Natural History Museum.

The story of Dinosaur Ridge began on March 26th, 1877. School of Mines professor Arthur Lakes was out with a friend when they discovered massive arm bones of what would later be named as the first Apatosaurus.

Over the next two years, Arthur Lakes would uncover hundreds of bones from Colorado’s most iconic dinosaurs and put our little town of Morrison on a much bigger map. Working with famous American paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh, the fossils Arthur Lakes uncovered were shipped east to the Yale Peabody Museum where most still reside. Some of these specimens, however, can be seen when the Morrison Natural History Museum reopens after this crisis.

These finds kick-started the aptly-named,"Bone Wars" between O.C. Marsh and other American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope. Our bones were the first in a discovery war waged between these two prominent scientists which was fueled by fame and jealousy. Spying and sabotage were their trademarks across the fossil-filled west between 1877 and 1892.

Welcome to Dinosaur Ridge!

You are at the West Gate Kiosk starting point, located on the Red Rocks side of Dinosaur Ridge.

On your journey today you will learn about the lives and deaths of our backyard dinosaurs and the different environments they roamed. This audio tour will describe and interpret 13 stops, indicated by posted signs as you walk along the 1 1/10 mile Dinosaur Ridge paved trail. We recommend that each member in your party download the tour to their own device for a more individual self-paced tour experience.

Please be prepared to walk 2 1/2 miles round-trip with an uphill climb for half of your journey. THERE ARE NO FACILITIES OR WATER ALONG THE TRAIL (with the exception of one port-a-potty near the top of the curve). Be sure to dress for the changing weather and bring sunscreen and water with you.

NOTE: for your safety, pedestrians must walk in the designated lane closest to the mountainside. The outermost lane is used by bicyclists, who often travel at high speeds over Dinosaur Ridge. Please observe all posted signs and beware of rattlesnakes coming out of hibernation. Climbing and collecting are NOT allowed. Dinosaur Ridge fossils are protected by the state of Colorado as Dinosaur Ridge is a National Natural Landmark and a unit of the National Park System.

DUE TO COVID-19, THE FOSSILS AND TRACKS SHOULD NOT BE TOUCHED, AND SOCIAL DISTANCING OF 6-FEET BETWEEN UNRELATED PARTIES SHOULD BE OBSERVED.

This audio tour was created by the nonprofit Dinosaur Ridge organization. To learn more about how you can support our efforts in protecting these unique resources, visit our website at www, dot dinoridge, dot org.

You may begin your walk on the inside lane uphill to our next stop called The MORRISON BONE BED.

As you begin your walk uphill, here is some information:

Dinosaur Ridge is part of the Dakota Hogback, the prominent ridge that parallels the Front Range of Colorado’s mountains. The term “hogback” is used in geology as a hill with a narrow crest and steep slopes on both sides that is capped by harder ragged rock.

Dinosaur Ridge is made of layered sedimentary rocks called sandstone and mudstone. The softer mudstone erodes quicker than the harder sandstone, which you can see when looking to the top of the ridge.

The layers you see here on this West Side are underneath and the oldest layers of Dinosaur Ridge, at 150 million years old. They are the last layers of the Jurassic Period (the middle period of the Age of Dinosaurs). The rocks show a semi arid floodplain with seasonal rivers and lakes, and more tracks from dinosaurs and even their bones can be seen.

The layers on the east side after you walk up and around the curve in the road are 100 million years old, the beginning of the Late Cretaceous (the last period of the Age of Dinosaurs). During this period, the Front Range was not mountainous, but a shoreline with sandy beaches and flats where prehistoric critters walked and left behind thousands of traces.

Closest City or Region: Dinosaur Ridge, Colorado

Coordinates: 39.686240, -105.193094

By Jeremy Dye

Jeremy Dye, Tara Dye, Savannah Dye, Cooper Dye, Greg Dye, Arianne Dye, Miller Dye,

Dad took the bus tour while the rest of us took the walking tour. We paid for the audio tour, which was well done. It was nice to be able to listen to the information while walking between the stops. We were very impressed with the dinosaur tracks and the fossils and had a great time.