Hype:

Norris Geyser Basin is one of the hottest and most dynamic of Yellowstone's hydrothermal areas. It is divided into two parts: Porcelain Basin and Back Basin. Steamboat Geyser is the tallest active geyser in the world. There are lots of other geysers and hot springs.

Trail Condition: Class 1 (Trail is either paved or gravel. Navigation skills are not needed because there is only one trail or because there are signs. Elevation gains are gradual or there are stairs.)

Time: up to 3 hours

Length: 3 miles round trip to see everything, shorter paths are available

Fees: Entrance fee

Recommended Ages:

| 0-3 |

| 4-11 |

| 12-19 |

| 20-49 |

| 50-69 |

| 70+ |

Recommended Months to Visit:

| Jan |

| Feb |

| Mar |

| Apr |

| May |

| Jun |

| Jul |

| Aug |

| Sep |

| Oct |

| Nov |

| Dec |

Navigate to 44.726067, -110.701988.

The following information was taken from the Norris Geyser Basin Trail Guide![]() , which is available at the trailhead.

, which is available at the trailhead.

Norris Geyser Basin is one of the hottest and most dynamic of Yellowstone's hydrothermal areas. Many hot springs and fumaroles have temperatures above the boiling point (200°F) here. Water fluctuations and seismic activity often change features.

It's hard to imagine a setting more volatile than Norris. It is part of one of the world's largest active volcanoes. And it sits on the intersection of three major faults. One runs from the north; another runs from the west. These two faults intersect with a ring fracture from the Yellowstone Caldera eruption 640,000 years ago. These conditions helped to create this dynamic geyser basin.

Each year at Norris new hot springs and geysers appear; others become dormant. Geologic events cause many of these changes. Even small earthquakes can trigger changes in hydrothermal behavior. Some changes are brief; others last longer.

Geysers and hot springs may also create changes in themselves. Some Norris hot springs, like Cistern, rapidly dissolve underground rock. As hot water moves toward the surface, the dissolved minerals deposit along subterranean passages and around the surface vents. Eventually, these deposits can choke off the flow of water. New features may be born as hot, pressurized water seeks a route to the surface.

Some features in Norris Geyser Basin can undergo dramatic behavioral changes simultaneously. Clear pools become muddy and boil violently, and some temporarily become geysers. Geysers cease erupting or have altered cycles. New features appear. This sudden activity is known as a "thermal disturbance" and can last a few days or more than a week. Gradually, most features return to "normal."

Why this happens is not fully understood. Norris has the greatest water chemistry diversity among Yellowstone's hydrothermal areas. Multiple underground hot water reservoirs exist here and as their water levels fluctuate, concentrations of chloride, sulfate, iron, and arsenic change. Although Norris is known for its acid features, it also has alkaline hot springs and geysers. As underground waters and chemistry shift, they could contribute to sudden dramatic changes in minerals and pH. Further study will help unravel the mystery of this phenomenon.

Many of the colors you see here are evidence of thermophiles (heat-loving microorganisms) and their activity.

Yellow deposits here typically contain sulfur. They form when hydrogen sulfide gas (the rotten egg odor you may have noticed) is converted to sulfur. Some thermophiles live in these areas because they use chemicals like sulfur for energy. They form communities of mats and streamers (formations that look like waving clumps of hair) in the hottest acidic runoff, which measure between 140°F and 181°F.

Dark brown, rust, and red colors abound in Norris and contain varying amounts of iron. Red-brown mats may also contain bacteria and archaea that help build the mats by metabolizing and depositing iron. These iron-oxide deposits often contain high levels of arsenic. These communities form in water below 140°F.

Emerald-green mats color many of the runoff channels of hot springs and geysers here. Algae are the dominant life forms in these mats and contain chlorophyll, a green pigment that helps convert sunlight to energy. Some bacteria and archaea grow in these mats, which form below 133°F.

Dark blackish-green mats form in even cooler water. An alga called Zygogonium forms these communities of mats and streamers.

Color placement within thermal water changes, in part, because temperatures and chemistry change. In a hot spring, for example, the hottest water is closest to a hot spring's vent. As the water flows outward, it gradually cools. This range of water temperature, called a thermal gradient, supports various thermophilic habitats. Chemical composition also changes as water flows from thermal features, mixes with other water sources, and is diluted or concentrated. As temperatures or chemical compositions change, microbial populations?and the colors they create?shift to a location they favor.

Norris Geyser Basin supports an astounding diversity of life. The majority of species here are microscopic thermophiles?heat-loving microorganisms. They survive in conditions of high heat and acidity or alkalinity that would instantly kill most other life forms.

Thermophiles are included in all three domains of life:

Bacteria This domain includes bacteria that can cause disease, fertilize soil, recycle material, and renew supplies of oxygen, nitrogen, and water. At Norris, some bacteria metabolize iron and other minerals.

Archaea The organisms in this domain were once considered bacteria, but their genes show they are as different from bacteria as they are from animals and plants. Scientists think they evolved long ago when earth's environment was much hotter. Many of the microbes in Norris are archaea.

Eukarya Within this domain are plants, animals, and fungi. Some of Norris's thermophiles?algae?also belong in this domain.

Viruses, which are not included in the three domains, also thrive in Yellowstone's hydrothermal features. The viruses here are different from other known viruses because they survive such extreme conditions.

Due to Norris Geyser Basin's rough terrain and highly changeable conditions, please expect uneven ground and steep grades that exceed 8 percent. Rocks and roots protrude into sections of dirt trail. Most of these sections are marked on the map, but may change. Proceed with extreme caution.

If you are staying in Norris Campground, a 1-mile trail connects the campground and geyser basin. This unpaved trail is mostly flat, well marked, and easy to follow. The geyser basin parking lot is typically full throughout summer, so using the trail can save you time and gasoline and help ease parking congestion.

If you began your visit at the geyser basin and wish to visit the Museum of the National Park Ranger, a historic soldier station, we suggest you use this connecting trail. An excellent view of the station, along with an exhibit, can be found at the turnout located on the main road approximately 1/2 mile (0.8 km) north of Norris Junction, on the road to Mammoth Hot Springs.

All of Yellowstone's hydrothermal areas are fueled by magma (molten rock) beneath the park. This magma heats water percolating down from the surface along fractures and faults. This superheated water rises back toward the surface, collecting into larger channels that serve as the "plumbing" for each hydrothermal feature.

Geysers form if the plumbing channel contains a constriction. Between eruptions, temperatures in the superheated, pressurized water beneath the constriction build up, creating increasing amounts of steam. Eventually the steam pushes water out of the constriction, water pressure deep in the system drops instantaneously, and the geyser erupts.

Hot springs are features with no plumbing constriction. Superheated water cools slightly as it reaches the surface, and is replaced by hotter water from deeper sources. This sets up a pattern of water circulation, which helps prevent the chain reaction leading to an eruption.

Fumaroles (steam vents) are Yellowstone's hottest surface features. Their underground channel systems penetrate the hot rock masses, but are generally dry. What little water does drain into the fumarole's plumbing converts instantly to steam.

Mudpots form when acid decomposes surrounding rock into clay. This clay mixes with water to form mud of varying consistency and color. Gases bubble and burst through the mud and create the playful plopping so characteristic of these features.

Rainbow colors, hissing steam, and pungent odors greet your senses in Porcelain Basin. This basin pulsates from steam and boiling water beneath the surface. Its features appear and disappear often, but some hot springs and geysers have become relatively stable features.

Take it all in from Porcelain Basin Overlook. You might see a small geyser splashing, sometimes two or three, sometimes none. Notice the milky blue pools?they are saturated with silica, which is the primary component of glass. Norris's thermal waters contain the highest concentration of silica in Yellowstone. Some of the orange color results from minerals containing elements such as iron and arsenic. Thermophiles also create colors you see, such as orange, greenish-black, and emerald green.

As you descend into Porcelain Basin, you'll pass Black Growler Steam Vent, a steady column of steam. A strong steam vent has been in different locations on this hill for many years, and it has always been called Black Growler. No one knows why it disappears and reappears, but Black Growler always roars back.

The boardwalk across Porcelain Basin takes you over hot, acidic waters.

It also provides a place to observe thermophile communities such as the streamers and mats populated by Zygogonium, an alga dark on the surface but bright green beneath. It thrives in water of pH 2-3 and temperatures of 68-96°F. Also look for the movement of ephydrid flies and other insects feeding off thermophile communities.

Constant Geyser could catch you by surprise. Its eruptions burst 20-30 feet high but last barely ten seconds. One or more erupt ions may occur within a few minutes of each other; the geyser may be quiet for 20 minutes or several hours.

When Whirligig Geyser erupts, its pulsing sound often can be heard around the basin. Its rust-orange color comes from iron that has been oxidized, in part, by thermophiles.

Pinwheel Geyser, seen from the overlook beyond Whirligig, hasn't erupted for many years. But its runoff channel provides one of the clearest thermal and chemical gradients in Norris. The brilliant green belongs to acid-tolerant thermophiles, including Cyanidium. This community begins when water cools to l00-126°F. Rust-red mats are colored by iron oxide. The boundary between green and brown mats occurs when acid-tolerant algae reach their upper temperature limit.

Return to the main path and continue around the lower part of Porcelain Basin. Look for tracks of bison and elk in damp areas.

You'll pass Whale's Mouth, which is currently a quiet spring,

and Crackling Lake, named for the popping sounds from springs on its southern shore.

The lodgepole pines to your left were killed by thermal activity. Silica penetrates the trees and hardens their bases.

From the wooded hill, you can see other geysers and hot springs near Black Growler Steam Vent.

When you reach the asphalt path, turn right and then left onto a trail leading to Congress Pool.

This hot spring was named in 1891 when scientists from around the world converged upon Yellowstone for the Fifth International Geological Congress. Its activity varies from a steaming, dry vent to a boiling murky hot spring to an over-flowing blue pool. It was one of the first pools discovered to contain Sulfolobus, a thermophile that uses sulfur for energy and turns hydrogen sulfide to sulfuric acid in hot acidic water. Newly discovered viruses have been found using Sulfolobus as their host.

At the junction, turn right to find Porcelain Springs, an ever-changing area. It may be full of water from new springs or geysers, or it could be dry and quiet.

As you circle back across Porcelain Basin, look for small patches of brilliant blue. They are salts containing sulfur, arsenic, and boron.

Hurricane Vent once rivaled Black Growler in steam and noise. It has also been boiling and full of steam, with a small waterfall on the far side.

Take your time on the steep climb back to the museum. Ledge Geyser may be spouting from its several vents. Its rare eruptions send water 80 feet or more over the basin.

In contrast to Porcelain Basin, Back Basin is forested and its features are more scattered and isolated. Notice the young lodgepole pines growing up among the remains of a fire that burned through the area in 1988. Their abundant growth provides ample evidence of the resiliency of Yellowstone's ecosystem.

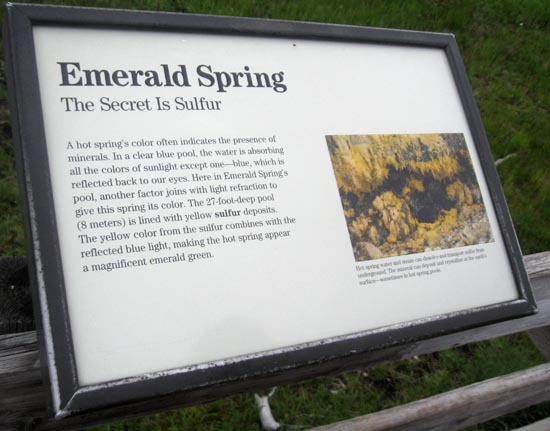

The magnificent color of Emerald Spring comes from the inherent blue of the water combined with the yellow of the sulfur-coated pool. The water in this 27-foot deep pool is so hot?close to boiling?that only the most heat-tolerant thermophiles can survive.

In sulfur-rich hot springs, such as Emerald Spring, some microorganisms use sulfur as their energy source. Byproducts from these reactions can be used by other microbes. This kind of "recycling" ties the various microorganisms into diverse functioning communities.

Days, months, or years pass between the major eruptions of Steamboat Geyser. The world's tallest active geyser, Steamboat throws water more than 300 feet high, showering viewers and drenching the walkway. For hours following its rare 3-40 minute major eruptions, Steamboat thunders with steam. As befitting such an awesome event, full eruptions are entirely unpredictable. More commonly, it ejects water in frequent bursts of 10 to 40 feet.

Cistern Spring and Steamboat Geyser are linked underground?a fact confirmed in 1983 when Cistern began emptying after each major eruption of Steamboat. Otherwise, Cistern is a beautiful blue pool with constant overflow. Its waters deposit as much as 1/2 inch of sinter each year. Look at the trees around and below this spring; the silica-rich water of Cistern is slowly killing them.

As you walk up to Echinus, notice the boiling pools on the hill. Black Pit Spring began as a group of small steam vents in the mid 1970s.

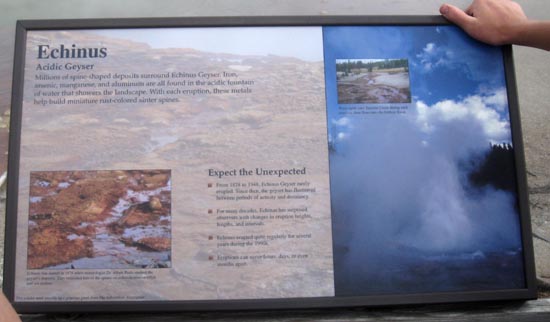

Echinus (e-KI-nus) Geyser is named for its deposits, which look like the spines of echinoderms such as sea urchins or sea stars. Iron oxides cause the red-orange color around the pool and along the runoff channel. Echinus is the largest acidic geyser known; its waters are pH 3-4, almost as acidic as vinegar. Its eruptions are now months to years apart, but could become frequent again. The viewing platforms accommodated crowds that gathered when Echinus was frequent and predictable.

After Echinus, the walkway takes you past a number of hydrothermal features. You are traversing dangerous ground. Do not leave the walkways?boiling water may lie beneath the ground.

Puff 'n Stuff Geyser often chugs and sprays water a few feet.

Although you can observe the steam from Green Dragon Spring from the main path, descend the lower path to fully appreciate its bubbling gassy water and to glimpse its sulfur-lined cave.

Blue Mud Steam Vent, which began as a powerful steam vent, can still be muddy and dry?or muddy and overflowing.

Yellow Funnel Spring often is roiling and murky. It can also be calm and clear, or dry and steamy. At one time, its pool was lined with sulfur, which accounts for its colorful name.

Beyond Yellow Funnel, the trail begins a route new in 2004. Previously, it crossed the flats to Pearl Geyse r. However, in 2003 this area became superheated?enough to begin toasting boardwalks and overheating visitors' feet?and a new feature began throwing scalding, acidic mud onto the trail. Ground temperatures continue to exceed 200°F, the boiling point of water at this elevation. The new route takes you around this area, behind Porkchop Geyser, and on to Pearl Geyser.

Porkchop Geyser was once a small hot spring that some people said occasionally erupted. It began spouting continuously in 1985. Then, in September 1989, Porkchop exploded, throwing rocks more than 200 feet. Afterward, it became a gently roiling hot spring. In July 2003, Porkchop roiled as if in eruption. This activity, which probably was caused by an increased discharge of carbon dioxide, ceased within a few days.

Pearl Geyser is a beauty?full or empty. Its eruptions can spray water 8 feet high. When it is empty, you can view its colorful formations and listen to its underground gurgling.

Between here and Tantalus Creek, the boardwalk passes Vixen Geyser, usually a slightly-steaming hole in the ground on the right side of the trail. If active, you may hear gurgling below the surface and see steam rising?or you may witness a brief, narrow, and tall eruption.

At the junction, turn right to view Corporal Geyser,

Veteran Geyser,

and Cistern Spring before ascending the steep stairs back to the museum.

Or go straight to view another small group of hydrothermal features. This route is longer but much less steep than the stairs.

Palpitator Spring seems to be constantly beating like your heart, with large "palpitations" caused by gas bubbles doming the surface. It has been known to drain completely for several hours, then refill and begin palpitating again.

According to PW. Norris, Monarch Geyser's eruptions in the 1880s shook the geyser basin and discharged huge amounts of water. Monarch remained active until the early 20th century, and resumed much smaller eruptions in the mid 1990s. An earthquake may have caused its increased activity, but the change was short-lived. Today it quietly overflows.

Minute Geyser spouts vigorously 1-3 feet above its crater?much less activity than during the time of stagecoaches. Visitors waiting for coaches amused themselves by tossing coins and other objects into the geyser. Over time, this vandalism plugged the geyser's plumbing, effectively killing it. No one can predict if Minute Geyser will ever again display its former power.

From here, the trail climbs slowly up the forested hill. Look for a short spur to the left, which takes you to an unnamed geyser.

After passing this feature, the trail begins to offer views of the East Fork of Tantalus Creek and Porcelain Basin, before reconnecting with the trail up to the museum.

Norris Geyser Basin is named for P. W. Norris, superintendent of Yellowstone National Park from 1877-1882. He recorded this area's features in detail. Norris also oversaw construction of some of the park's first roads, some following Native American trails.

Like other hydrothermal areas in Yellowstone, Norris provides a warm respite from winter for bison and elk. They can also find plants growing here year-round and water to drink.

Watch for bison in the spring; they can seem to suddenly appear as they walk about the basin.

Elk give birth to their calves in May. Do not approach calves; adults fiercely defend their young. Bull elk in the fall are also dangerous.

Look and listen for killdeer. They nest on bare ground and will call in alarm if visitors are close by. Also look for swallows, which fly over the basin catching insects to eat.

Norris Geyser Basin is home to many insects associated with thermophiles. It also provides habitat for colorful dragonflies. Look for them in grassy areas near Crackling Lake in Porcelain Basin and Puff 'n Stuff Geyser in Back Basin.

Closest City or Region: Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming

Coordinates: 44.726067, -110.701988

By Jeremy Dye

Cooper Dye, Greg Dye, Laura Dye, Anthony Dye, Arianne Dye, Miller Dye, Kingston Dye, Ondylyn Wagner, Jaren Wagner, Killian Wagner, Calliope Wagner,

Tara woke up around midnight with a sick stomach. She threw up a couple times in the wee hours of the morning and spent most of the night on the floor just outside the bathroom. Diarrhea hit a little bit later and she had an all-around rough go of it.

Shortly after breakfast, Madi started throwing up as well. She threw up all day long until evening. The two of them stayed at camp while I took Savannah and Cooper to Yellowstone with the rest of the group.

We made it as far as Gibbon Falls before Savannah started throwing up as well. She threw up all over the front of herself in the back of Ondy's car.

We got her cleaned up and proceeded to the waterfall where we shuffled around a bunch of stuff. I had left the truck at camp since we were fewer in numbers, so that meant that I had to drive Ondy's Jeep back to camp with Savannah.

It took us a lot longer than normal because we had to stop several times for her to throw up some more. We then spent the rest of the afternoon at camp with Savannah, Madi, and Tara trying to sleep in the trailer but being constantly interrupted by someone throwing up.

I made a lot of trips back and forth to the pit toilets to dump out throw up bowls. Tara started feeling mostly better by mid-afternoon or evening. Savannah stopped throwing up around mid-afternoon and Madi was throwing up until dinner time. The adults minus Tara talked around the campfire.

Cooper went with the rest of the group to Norris Geyser Basin, the Canyon Visitor Education Center, and Artist Point.

Oklahoma by the Playmill Theatre

Oklahoma by the Playmill Theatre

Canyon Visitor Education Center

Canyon Visitor Education Center

By Jeremy Dye

Jeremy Dye, Tara Dye, Savannah Dye, Greg Dye, Laura Dye, Zac Dye, Bryce Ball,

Brink of the Lower Falls Trail